It's 1942, and American soldiers are getting absolutely destroyed by mosquitoes in the Pacific jungles. Not just annoying little bites - we're talking about disease-carrying swarms that were literally killing more troops than enemy bullets in some areas. The military brass knew they had a serious problem on their hands, and conventional repellents weren't cutting it.

Enter Samuel Gertler, a scientist working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture who was about to accidentally create the most effective bug spray in history. What started as a desperate wartime project would eventually end up in every Canadian cottage, camping pack, and backyard barbecue across the country.

When Science Goes to War

The USDA and military weren't messing around. Between 1942 and 1947, they systematically tested over 7,000 different compounds, looking for the perfect mosquito deterrent. Scientists would literally stick their arms into cages containing 2,000 to 4,000 mosquitoes to test each potential repellent. Talk about taking one for the team.

DEET was developed in 1944 by Samuel Gertler of the United States Department of Agriculture for use by the United States Army, following its experience of jungle warfare during World War II, but it wasn't quite ready for prime time yet. Gertler received his patent on September 4, 1944, describing his vision for a repellent that would be:

"effective long after application, is not easily removed in adverse weather, is not harmful to humans or animals, and is not obnoxious in use."

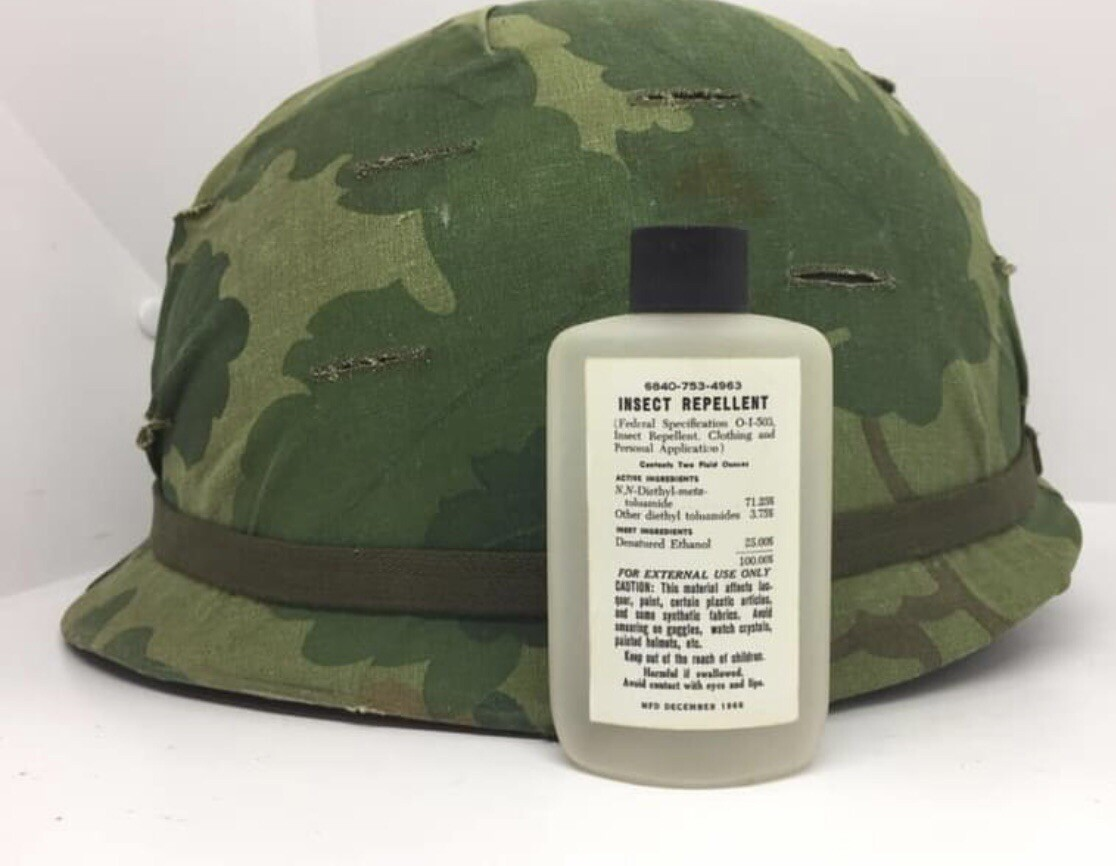

The stuff was initially tested as a pesticide on farm fields before anyone realized its true potential. When the military finally started using it in 1946, they called it "bug juice" - a fitting name for what was essentially 75% DEET mixed with 25% ethanol.

Imagine slathering that on your skin before a fishing trip.

From Battlefield to Backyard

It took another decade before civilians could get their hands on this wonder chemical. DEET didn't become available to the general public until 1957, years after the patent was actually granted in 1946. Once it hit the consumer market, though, it exploded.

Today, it's estimated that about 30% of Americans use DEET-containing products every year, with similar usage rates up here in Canada.

The transition from military to civilian use wasn't exactly smooth sailing. Early commercial versions came in various forms - creams, lotions, sprays, even powders. Companies started experimenting with different concentrations, ranging from single-digit percentages all the way up to 100% pure DEET. (Pro tip: you definitely don't need 100% concentration for a weekend at the lake - that stuff can literally melt plastic.)

What's remarkable is how DEET became the gold standard almost by accident. After completing a comprehensive re-assessment of DEET, the EPA concluded that it remains one of the safest and most effective repellents available. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still recommends 30-50% DEET concentrations for preventing insect-borne diseases.

The Mystery That Still Bugs Scientists

Here's where it gets really interesting: after more than 75 years of use, scientists still aren't completely sure how DEET actually works. The prevailing theory used to be that it simply blocked mosquito smell receptors, kind of like putting a clothespin on their nose. But recent research suggests it's way more complicated than that.

DEET is a multitasking compound. First and foremost, it is a repellent sensu stricto, meaning it's both an odorant that mosquitoes smell and avoid, plus something that tastes terrible when they make contact with treated skin. Some researchers think DEET might actually mimic natural plant compounds that insects have evolved to avoid over millions of years.

What's Next for Bug Defense

The search for DEET alternatives is heating up, partly because the stuff isn't cheap for people in areas where mosquito-borne diseases are a daily threat. Researchers at UC Riverside for example have identified compounds in fruits like plums and oranges that could potentially work as well as DEET while smelling way better. "One of them is present in plum," he says.

"The other is present in orange and jasmine oil. Some of them are present in grapes. And, as you can imagine, they smell really nice."

Picaridin is another chemical that's approved in Canada to repel insects, though without the oily feel. It's about as effective as DEET (if not a bit better), though it has some quirks.

There's even talk of repellents that could be thousands of times more effective than DEET, though those are still years away from hitting store shelves.

For now, though, Samuel Gertler's accidental invention remains the go-to choice for anyone heading into mosquito country - AKA anywhere in Canada. Not bad for a chemical that started life as a potential farm pesticide and ended up saving countless camping trips, cottage weekends, and outdoor adventures across Canada.

Next time you're spraying on that familiar-smelling repellent before hitting the trails, remember you're using technology that helped win a war - even if the only enemy you're facing is a persistent cloud of blackflies on the Rideau Trail.

Join the Conversation