The blacklegged tick, notorious for carrying Lyme disease, used to die in Canadian winters. Now, it thrives.

This reality should worry you.

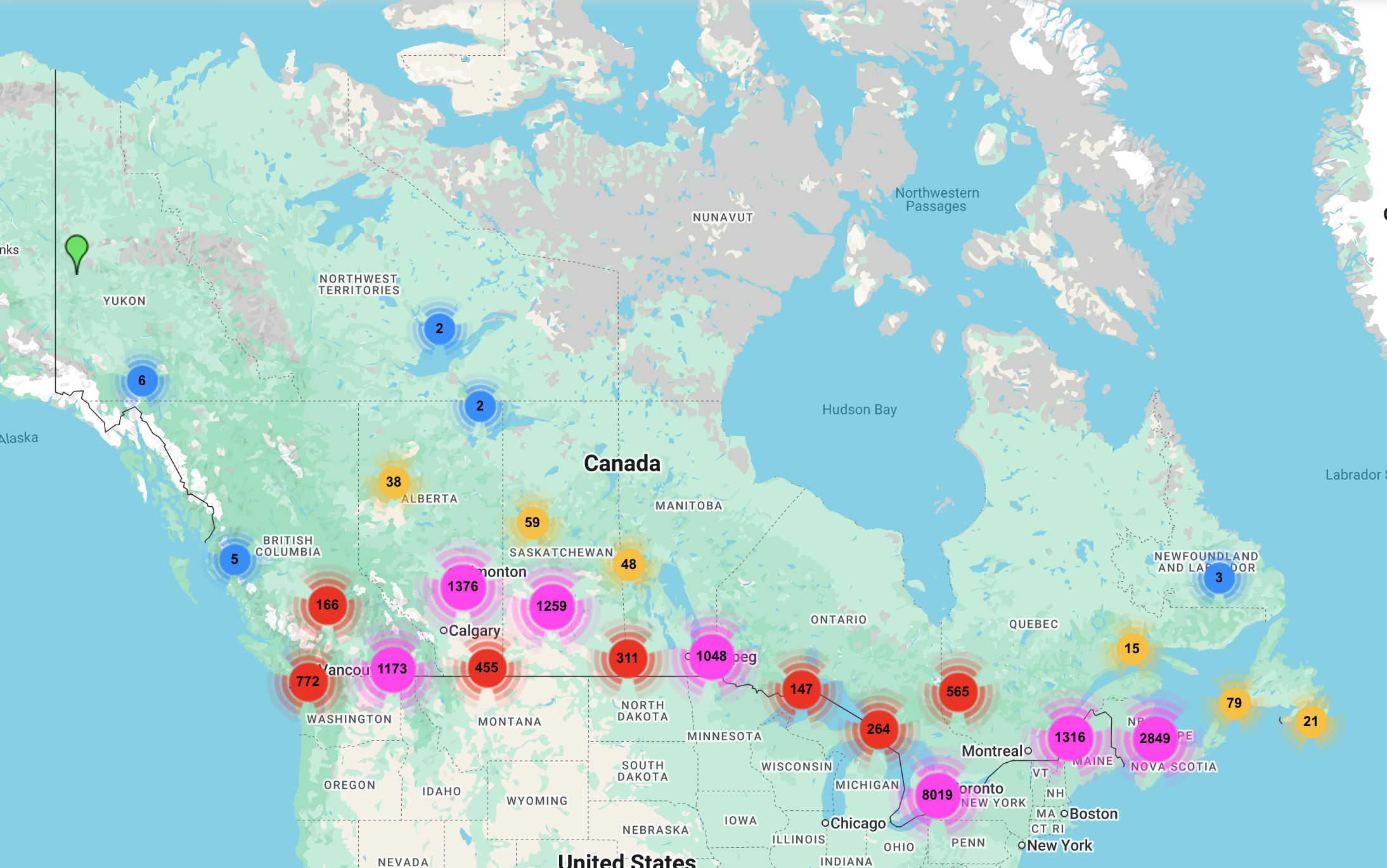

Lyme disease cases have exploded from just 144 in 2009 to over 5,200 in 2024. What was once a minor concern for southern Ontario cottagers has become a nationwide health crisis.

Lyme Disease Cases in Canada

Number of reported human cases from 2009 to 2024

Total cases (2009-2024)

27,463

Increase from '09

+3,538%

*2024 data is preliminary

Source: Public Health Agency of Canada

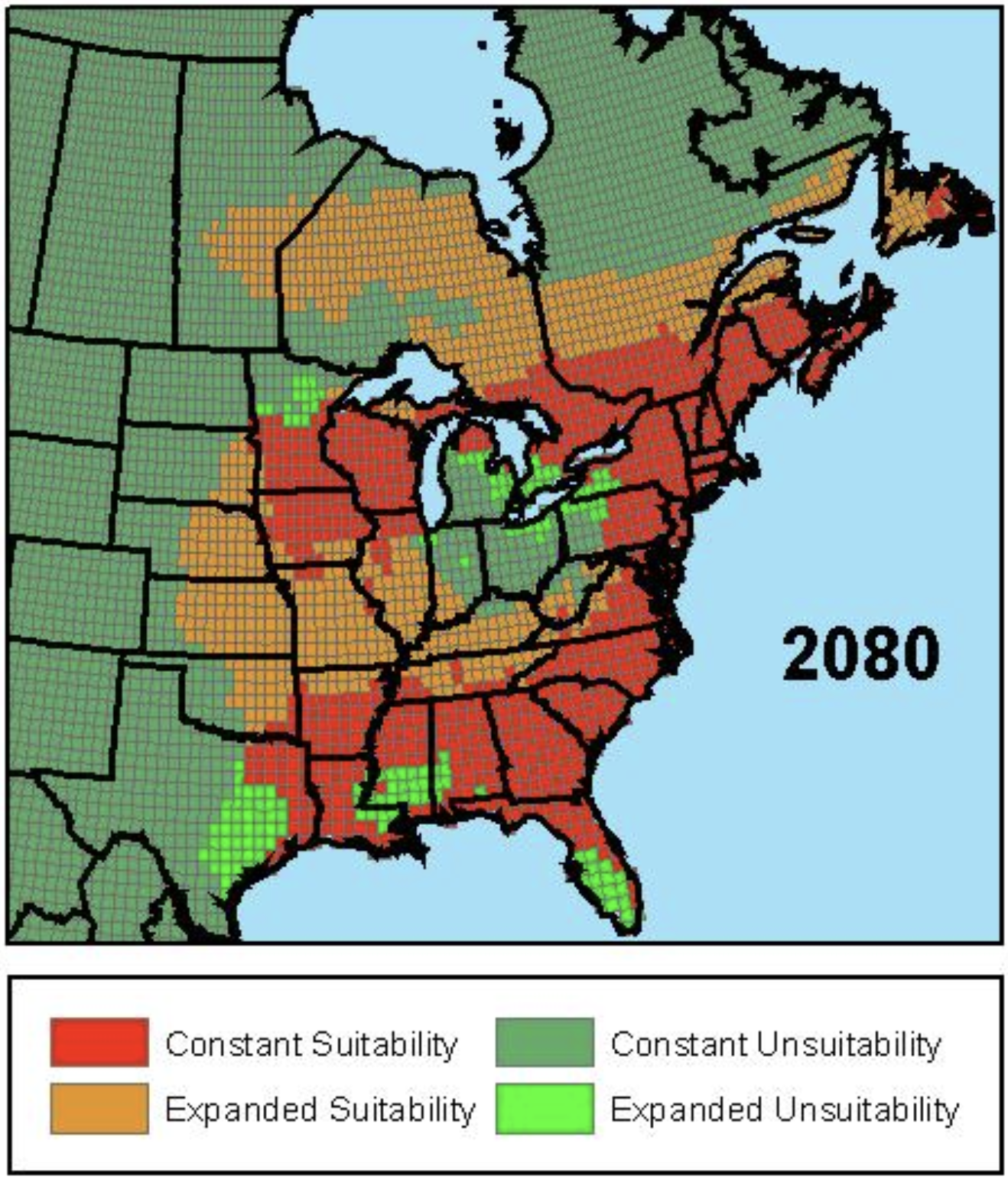

What's worse? The area where Lyme-carrying ticks are found is expanding northward at 35-55 kilometers per year.

"The single most important factor for the growth in tick populations across Canada is warmer temperatures," according to Nicholas Ogden, a senior research scientist at the Public Health Agency of Canada in an interview with the CBC.

His models predicted this expansion decades ago, but even he seems surprised by the speed

We see essentially an epidemic of Lyme disease in Canada and in North America, a changing range that is driven in part by a warming climate that has allowed these ticks to invade into new environments.

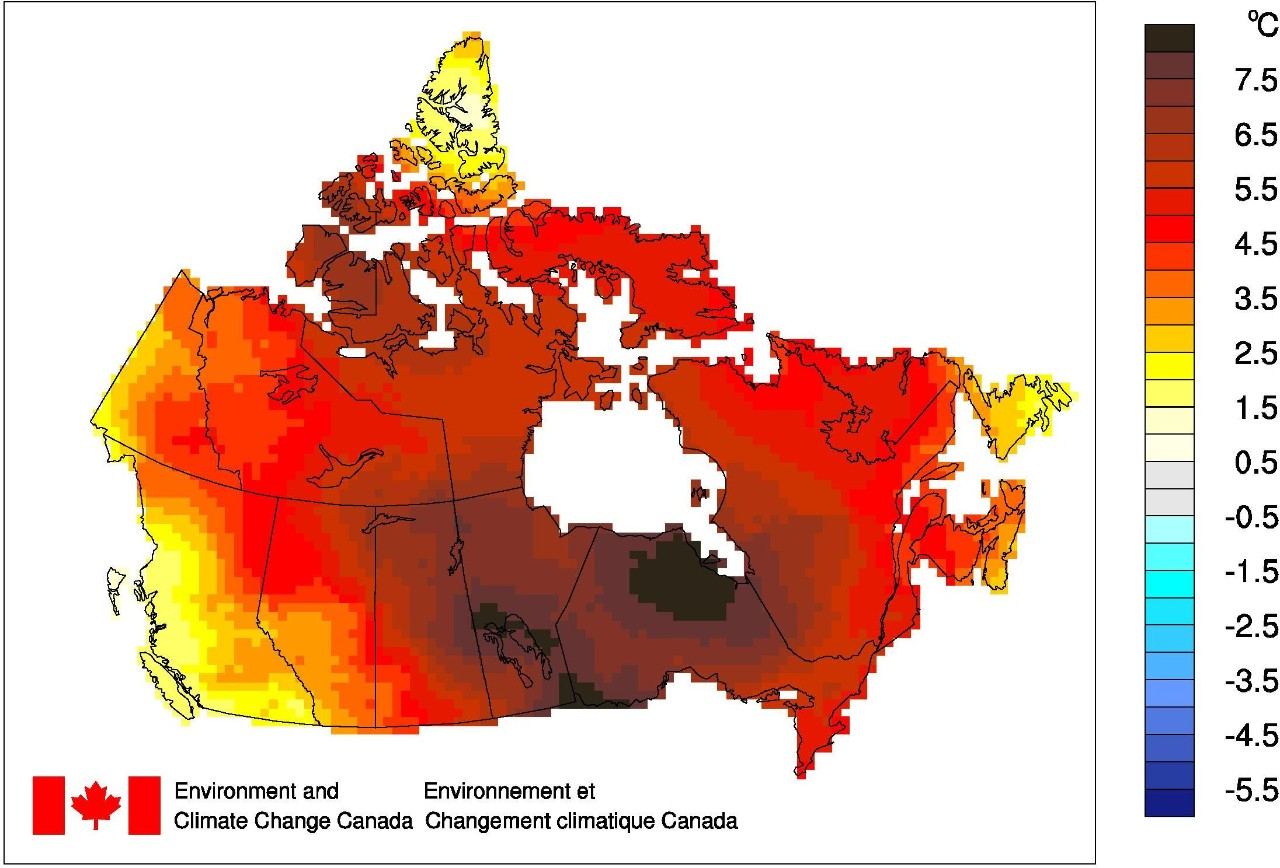

With Canada warming at twice the global rate, our cherished outdoors culture is directly in the path of an ecological invasion.

Your cabin isn't as safe as it used to be

The numbers paint an alarming picture for anyone who owns property outside of Canada's cities.

With some Lyme-carrying ticks surviving winter down to -20°C, every degree matters.

High Risk Lyme Disease Areas in Canada

High-risk FSAs from PHAC 2024 data

Total high-risk FSAs

Loading...

Coverage

Loading...

Click on any postal area for details. Zoom in to see postal code boundaries.

Source: Public Health Agency of Canada

Winter temperatures in Canada have increased by 3.6°C over the past 77 years, with the winter of 2023/2024 being the warmest on record at 5.2°C above baseline. More areas across the country are becoming a suitable year-round home for disease carrying ticks.

Odds are better than not that your postal code falls in the high risk category.

The temperature where ticks become active and begin questing - searching for a blood meal - is just 4°C. Ticks can now remain active during mild winter days and emerge earlier each spring.

In Muskoka, once considered too cold for established tick populations, blacklegged ticks now thrive. The Kawarthas, Haliburton, and Georgian Bay regions all report growing tick populations. Quebec's Laurentians and Eastern Townships face similar invasions. Even Manitoba's lake country, historically tick-free, saw tick density triple between 2000 and 2015, jumping from 36 to 110 ticks per square kilometer.

Dr. Kieran Moore, Ontario's Chief Medical Officer of Health, doesn't mince words about what's coming.

It's absolutely expected that we'll have greater incidence [of Lyme Disease] over the next several years because this is a known wave of infections that we've seen migrate up the coastline of northeast North America.

The wave he describes isn't hypothetical. It's already happening.

A threat multiplying

The expansion isn't linear; it's exponential.

Nova Scotia provides the starkest example: its first case of Lyme disease was only reported in 2002. Now, the entire province has been declared endemic, with Lyme disease infection rates reaching 32 cases per 100,000 people.

That's nearly five times the national average.

One in five ticks in the Maritimes now carries the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

Kateryn Rochon, an entomologist from the University of Manitoba said in an interview with Manitoba Co-operator:

I talk to producers when I'm out on their land to get ticks, and they would say, you know I never saw ticks when I was growing up—I've been here all my life and never saw ticks, and now they're everywhere.

Conservative estimates suggest Canada could see 120,000 annual Lyme disease cases by 2050.

By 2080, tick-suitable habitat will expand by nearly 70%, potentially reaching Hudson Bay.

Katie Clow, an assistant professor in population medicine from the Ontario Veterinary College explained the mechanism in an interview with the CBC:

"As the climate warms, these ticks that are constantly being introduced by birds are being introduced into places that were previously not suitable for their survival - but are now suitable."

Once a tick population establishes, it takes just five years for the Lyme disease transmission cycle to fully develop.

Though dangerous, Lyme is curable

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection. Borrelia burgdorferi is the name of the bacteria that causes Lyme disease through tick bites.

Infected ticks typically must be attached for more than 24 hours before causing infection. This means your chance of contracting Lyme disease is low if you are able to find and remove an infected tick on the same day that it attached itself.

The characteristic erythema migrans rash appears in 70-80% of cases of Lyme disease in Canada - but doesn't always look like the classic "bull's eye", pictured below.

Early symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue, and muscle aches.

Without treatment, long-term complications can include arthritis, facial palsy, and rarely, heart problems.

Fortunately, Lyme disease is a bacterial infection that's curable with a short course of antibiotics - usually an oral medication, doxycycline, for two or three weeks.

Misinformation a growing threat

Almost as concerning as tick expansion is the spread of Lyme misinformation.

Lyme literate providers are often non-physicians who promote the idea that - despite negative testing and no evidence of infection - vague symptoms such as fatigue and brain fog represent "chronic Lyme disease" that needs to be treated with long-term antibiotics or costly, unproven therapies.

They also argue that standard testing for Lyme disease in Canada is flawed.

The truth? Lyme disease is a bacterial infection that all physicians in Canada are trained to diagnose and treat with appropriate antibiotics.

And Canada's modified two-tier testing (MTTT) approach offers excellent accuracy with 99.5% specificity and sensitivity of 60% in early disease, rising to nearly 100% in systemic disease.

The medical consensus from Canada's infectious disease physicians and international medical organizations is clear:

Prolonged antibiotic treatment promoted for persistent symptoms attributed to Lyme disease should not be used.

They don't improve outcomes and can cause severe harm - and even death.

Persistent symptoms are rare, but can happen

Some people do continue to experience symptoms after treatment of confirmed Lyme disease; this is referred to as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS) and is an area of active research. Current evidence suggests that these symptoms result from residual tissue damage - not ongoing infection.

Fortunately, PTLDS is rare and the vast majority of patients with Lyme disease are symptom-free after completing a short course of antibiotics.

Red flags

Be cautious of these warning signs if you or someone you know is being evaluated for Lyme disease:

- Repeated testing despite negative results from Canadian labs

- Non-licensed international labs with high (50%+) false positive rates

- Non-physician (MD) practitioners claiming special "Lyme literacy"

- Expensive, unproven treatments costing tens of thousands of dollars

The real danger of attributing symptoms to Lyme disease when there's no evidence to back it up? Missed cancer diagnoses, delayed MS treatment, or even death from unnecessary treatments.

Talk to your family physician and trust Canada's world-class evidence-based public health system. If you have persistent symptoms, work with your doctor to explore all possibilities - and avoid falling prey to those profiting from fear and false hope.

Beyond Lyme

While society has a special fascination with Lyme disease, other tick-borne illnesses advance northward in its shadow.

Anaplasmosis cases in Ontario jumped to 40 in 2023.

Babesiosis, which attacks red blood cells, now appears regularly.

Perhaps most concerning is Powassan virus, which Dr. Michelle Murti, Associate Chief Medical Officer of Health for Ontario, warned in an interview with the Canadian Press can cause permanent damage:

Approximately 50 per cent of people who survive severe disease have long-term health problems, such as recurring headaches, loss of muscle mass and strength, and memory problems.

These aren't exotic tropical diseases anymore.

They're establishing themselves in the mixed forests and woodland edges that define Canadian cottage country - right where we build our decks, sit around our fire pits, and watch our children play.

Fighting against an eight-legged invasion

The expansion feels inevitable, but Canadians aren't helpless.

Creating a barrier of wood chips or gravel between your lawn and the forest can dramatically reduce tick encounters. Strategic landscaping matters too; beautiful but overgrown naturalized gardens create perfect tick habitat. Japanese barberry and buckthorn, common invasive species around older cottages, are tick magnets.

Daily tick checks should become as routine as locking doors. Focus on warm, hidden areas: behind ears, hairline, armpits, and groin.

Ticks need 24-48 hours of attachment to transmit Lyme disease, making prompt removal critical. Save any removed tick in a sealed container - and send a photo to eTick.ca to help track spread.

In terms of prevention, permethrin-treated clothing provides weeks of protection, and DEET remains the gold standard for repelling ticks. Picaridin is a newer option that may be more effective against mosquitos, and is equally effective against ticks when compared to DEET.

But these personal measures only work with consistent application.

As Dr. Rochon emphasized in an interview with the CBC:

It's important to still go outside, and not be afraid of going outside. You just need to adapt your behavior, protect yourself, and be aware of the risks.

This is our new reality

We're not talking about a future threat to Canadian life - it's a current crisis measured in rising case counts and expanding risk maps.

Every mild winter, every early spring, and every late fall extends the tick season and expands their territory. Ticks that once died at the US border now establish populations wherever our warming climate allows.

The question isn't whether tick-borne diseases will reach your cabin or cottage; it's when.

For many regions, that answer is already "now." For others, it's measured in years, not decades.

We can still enjoy our cottages, still treasure our time in nature, and still pass these experiences to our children. But climate change has armed nature with a new threat that expands its territory with every degree we warm.

Because the ticks aren't coming.

Join the Conversation